Monuments

- Dipylon Krater, 5-2

- Title

- Artist

- Period Geometric

- Provenance Dipylon Cemetery, Athens, Greece

- Date 750 BC

- Material Pottery

- Kroisos, Kouros from Anavysos, 5-9

- Title

- Artist

- Period Archaic

- Provenance Anavysos, Greece

- Date 530 BC

- Material Marble

- Peplos Kore, 5-10

- Title

- Artist

- Period Archaic

- Provenance Athens, Greece. Found at the Acropolis.

- Date 530 BC

- Material Marble

- Amphora by Exekias, 5-20

- Title

- Artist Exekias

- Period Archaic

- Provenance Attica, area around Athens. Found in Etruscan tomb.

- Date 530 BC

- Material Black figure pottery

- Athena, Herakles and Atlas, 5-33

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Classical

- Provenance Part of Zeus at Olympia Temple

- Date 470 BC

- Material marble

- Kritios Boy, 5-34

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Classical

- Provenance Athens, Greece. Part of Acropolis.

- Date 480 BC

- Material Marble

- Doryphoros by Polykleitos, 5-40

- Title

- Artist Polykleitos

- Period High Classical

- Provenance Polykleitos was from Argos, Greece. Popular Roman reproduction from Pompeii, Italy.

- Date 450 BC

- Material Original was bronze, surviving Roman copy is marble.

- Parthenon, 5-1, 5-42 – 5-45

- Title

- Artists Phidias, Ictinus, Callicrates

- Period High Classical

- Provenance Athens, Greece.

- Date 448 – 432 BC

- Material white marble, caustic paint, ivory and gold for statue of Athena.

- Panathenaic Frieze, 5-50

- Canceled.

- Nike, from Temple of Athena Nike, 5-56

- Title

- Artist

- Period High Classical

- Provenance Athens, Greece. Acropolis. (Roman Roman Reproduction)

- Date 410 BC

- Material marble, high relief.

- Hermes by Praxiteles, 5-63

- Title

- Artist Praxiteles

- Period Late Classical

- Provenance Found at Temple of Hera, Olympia, Greece.

- Date 340 BC

- Material Marble

- Altar of Zeus, Pergamon, 5-78, 5-79

- Title

- Artist

- Period Hellenistic

- Provenance Pergamon, Turkey

- Date 175 BC

- Material Marble

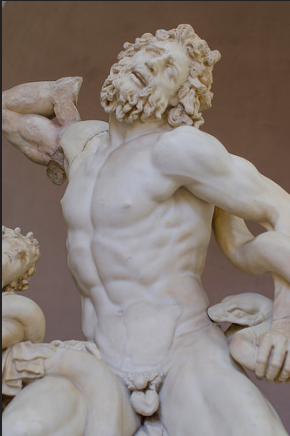

- Laocoon Group, 5-89

- Title

- Artist 3 Known Artists

- Period Hellenistic

- Provenance Rome, Italy

- Date 1st century AD.

- Material Marble

- Apollo of Veii, 6-4

- Title

- Artist

- Period Etruscan

- Provenance Veii, Italy.

- Date 510 BC

- Material Painted terracotta

- Capitoline Wolf, 6-11

- Title

- Artist

- Period Etruscan (babes added later)

- Provenance Rome

- Date 500 BC

- Material Cast bronze.

- Temple of Portunus, 7-3

- Canceled.

- Cubiculum, Boscoreale, 7-19

- Canceled.

- Augustus of Primaporta, 7-27

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Imperial

- Provenance Primaporta, Italy.

- Date Sometime after 20 BC

- Material Marble, copy of bronze original.

- Pont-du-Guard, 7-33

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Imperial

- Provenance Nimes, France

- Spans Guard River

- Date 16 BC

- Material limestone

- Voussoir Arches

- Colosseum, 7-36, 7-37

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Imperial

- Provenance Rome, Italy

- Date 80 AD

- Material Concrete core covered in travertine. Timber flooring covered in sand. Marble seats for VIPs. Upper seating probably wooden benches.

- Seated 50,000 people.

- 76 barrel vaults

- Vespasian, 7-38

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Imperial

- Provenance Rome

- Date 80 AD

- Material Marble

- Arch of Titus, 7-40

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Imperial

- Provenance Rome, Italy.

- Date 80 AD

- Material Concrete and marble.

- Composite columns.

- Ionic and corinthian combined.

- Composite columns.

- Pantheon, 7-49 – 7-51

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Imperial

- Provenance Rome, Italy.

- Date 120 AD

- Material concrete, marble.

- Corinthian columns.

- Base, Column of Antoninus Pius, 7-57, 7-58

- Canceled.

- Tetrarchs, 7-73

- Title

- Artist

- Period Late Imperial

- Provenance Traced to Constantinople, looted in 1204.

- Date 305 AD

- Material Porphyry

- Arch of Constantine, 7-75

- Canceled.

- Old Saint Peters, 8-9

- Canceled.

- Santa Constanza, 8-11 – 8-13

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Christian

- Provenance Rome, Italy.

- Date 350 AD

- Material Concrete, plain brick facade. Glass mosaics on interior walls. Spolia (reused building materials.)

- Good Shepherd Mosaic, 8-17

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Christian

- Provenance Ravenna, Italy

- Date 425 AD

- Material Glass mosaic

- Diptych of the Nicomachi and Symmachi, 8-25

- Title

- Artist

- Period Early Christian

- Provenance Rome, Italy

- Date 400 AD

- Material Ivory, originally with wax on inside.

- High classical style.

- Vatican Vergil, 8-20

- Canceled.

Vocab

- Amphora

- Particular vessel shape.

- Wide mouth, bulbous body that flares to point.

- Used for storing liquids.

- Be able to draw.

- Amphora by Exekias

- Amphitheatre

- “Double theater”

- Like the Colosseum

- Arena

- Literally sand.

- Upon which gladiatorial combat took place.

- Like the Colosseum.

- Apotheosis

- When a mortal is transformed into a God.

- Like Column of Antoninus Pius

- Black figure/red figure

- Decoration on Greek pottery where coloring is result of firing process.

- Archaic.

- Amphora by Exekias

- Caryatid

- Female sculpture used as column.

- Like the Caryatid Porch in Athens.

- Contrapposto

- Relaxed standing

- Weight on one foot.

- Torso turned slightly.

- Kritios Boy

- Coffering

- A design made up of inset squares or other geometric shapes.

- Can be used to decrease the weight of a dome.

- Like the Pantheon.

- Capitol

- The building from which the government leads

- Something related to the Capitoline hill.

- Like the US Capitol building

- Constatinie

- Roman Emperor

- Originally one of the Tetrarchs.

- Son of one of the original Tetrarchs.

- Killed the other 3 tetrarchs and took power for himself.

- Legalized the practice of Christianity.

- Made Constantinople the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire.

- Entasis

- A style in which the shaft of columns appear to swell under the weight of a building.

- Can be very slight or very dramatic.

- Parthenon

- Encaustic

- Paint in which the pigment is mixed with melted wax.

- Kouros from Anavyssos

- Engaged column/pilaster

- Engaged column

- Decorative only

- Romans liked them.

- Like a relief sculpture of a column.

- Like Colosseum

- Engaged column

- Isocephaly

- Means “same head”

- All heads placed at same level in a composition.

- Typically for art placed on building.

- Visual level in harmony with building.

- Like Pantheon frieze

- Kore

- Archaic statue of young woman.

- Peplos Kore

- Kouros

- Archaic statue of young man.

- Kroisos Kouros

- Kylix

- Vessel for drinking wine at parties.

- Difficult to drink from.

- Controls drinking habits.

- Oculus

- “Eye”

- The round central opening of a dome.

- Pantheon

- Peripteral

- Building surrounded by columns

- Pantheon

- Lincoln Memorial

- Personification

- Representing idea/concept in form of human.

- Statue of Liberty

- Terracotta

- Orange, low fire ceramic material.

- Prefered material for Etruscan sculptures.

- Means cooked earth.

- Terracotta Army

- Tondo

- Round in Italian

- Means round composition in any medium.

- Inside of many kylixes

- Veristic

- Hyper naturalistic portraiture.

- Roman Republican portraiture.

Other:

What is Tuscan Order?

Similar to Doric Order, except columns smooth instead of fluted, and they have bases.

What in Corinthian Order?

Like the Ionic Order, except capital is different. Can be viewed the same from all four sides.

For extra credit, know styles.

Early classical:

-Not dynamic.

-Not revealing.

Classical Greek Art (Early classical?)

-Contrapposto

-More naturalistic

-Not completely frontal

Standards for classical

-Long straight nose

-Cupped prominent chin

-Strong prominent jaw

-Edge between eye sockets and forehead well defined.

-Full, rounded lips.

-Very smooth skin.

-The flesh itself is smooth.

High Classical

-Buffer

-More naturalistic

-More pronounced contrapposto

-Striding controposoto.

-Poses more naturalistic.

-More revealing clothing for females.

-Much more realistic drapery.

-Drapery used as element of design.

Late Classical

-Begins around 300 BC

-Corinthian order emerges.

-Female nudity in figure sculpture becomes acceptable.

-Little less muscular.

-Hair is more realistic.

-High relief, not just linear pattern.

-Softer features across whole body.

-A little more interest in expression.

-More three dimensional viewing experience.

Praxiteles

-Artist

-Signature s curve of upper torso leaning into engaged leg.

-Late classical.

Hellenistic

-More naturalistic

-More emotion

-Less rule oriented

-Longer hair (including facial hair)

-Eyes set back further in head.

-Deep undercutting creates dark shadows.

-Dramatic.

-Super human bodies.

-More chaotic composition